Explore the past, present, and future of flax.

Uses and Benefits of Flax Today

Flax benefits:

Easy to grow

Low-impact

Requires little-to-no chemical inputs or irrigation

Soil remediator

Protects waterways

Provides pollinator habitat

Easy and beneficial addition to crop rotations

Commercial uses:

Linen

Building material

Animal bedding

Industrial twine and rope

Canvas and webbing

Paper

And more

The Future of Flax in Pennsylvania

The most prolific growing region for flax, northern Europe and the Baltic states, is struggling to meet demand. Much of the region is now a warzone, and no flax was planted in 2022. Nearby northern France and Belgium lack the necessary land mass. A pending crop shortage combined with climate instability has made it increasingly difficult to guarantee crop quality.

With over 7 million acres of farmland in Pennsylvania, we can fill a major gap in the supply chain.

A single client might use 18,000 tons of retted flax straw annually, requiring 9,000 acres in production. Another producer we're building a relationship with represents 10% of global production of linen. They use 6-8,000 tons of scutched fiber annually. This equates to 18,000+ acres in production each year on the low end.

With that many acres in production, PA could support 4 to 5 scutch mills, opening even greater opportunity for economic growth in the region.

We are working to put 12,000 acres of organic fiber flax into production in PA

And this is only the beginning.

The History of Flax in PA: A Timeline

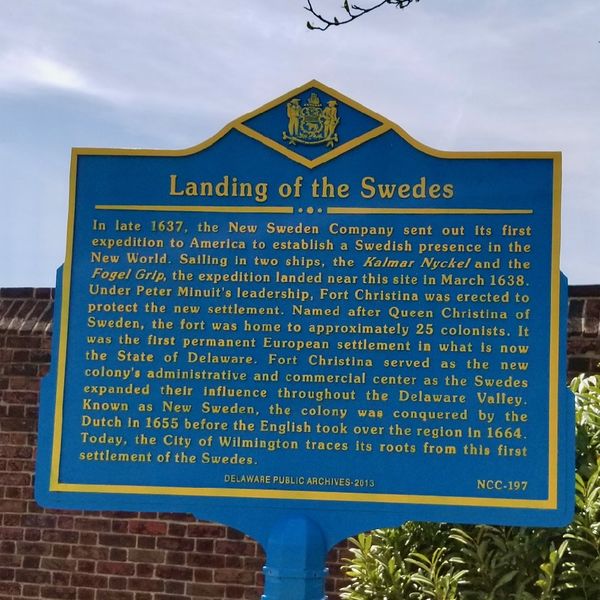

“The First Immigrants and Flax

Before Delaware was settled by European colonists the area was home to the Eastern Algonquian tribes know as the Unami Lenape or Delaware living along the coast. In 1638, the Swedes, Fins and Dutch established New Sweden, a Swedish Trading Post. They established Fort Christina to protect it. This colony lasted 17 years, with control of the area won and lost in battle resulting in Delaware, the same land William Penn once controlled and called Pennsylvania. Flax production began in the Delaware Valley with this Swedish settlement at Fort Christina. Earlier Dutch trading forts had probably depended completely on New Amsterdam for clothing. By the 1650s, flax was being raised, spun, and woven by its women (4).”

“Flax in the Early Colonial Period

By 1683, William Penn, then proprietor and governor, legislated for the farming and marketing of flax at the PA Provinicial council. Daniel Pastorius and 13 immigrating Mennonite and Quaker families settling Germantown, PA became some of the first major flax producers. Hints of this past can be seen in the Germantown “Town Seal” which includes a grape vine, flax blossom and wavers spool.”

“Colonial Self-Sufficiency in Textiles

The Germantown Fair, first held in 1701, became the center of exhibiting and selling the products of these craftsmen. “The Mennonites created independent economic villages learning to prosper in isolation” (Skrabec. 2014. p19).”

“Flax, Fabric, and International Trade

Immigration to Pennsylvania and transatlantic commerce developed. The 1740 flaxseed season saw in all 21 flaxseed ships including seven to Dublin (MacMaster, 2009, p49). Flaxseed was a major Pennsylvania export. Thomas Penn had an agent in Dublin in the 1740s selling flaxseed for him, which the Irish would raise process and then ship.”

“Emergence of the Early Colonial Textile Economy

With immigration, Phildelphia and its countryside develops. By the 1750s, 10-12,000 yards are woven yearly by six linen weavers working in the Brethren House. A store was built in 1753 to meet outside demand for Moravian products. From June 1758 to May 1759, over 4,500 yards were sold in return for such goods as flax and flaxseed.”

“Flax and the American Revolutionary Period

The Industrial Revolution develops and machine based textile production in factory setting begins to emerge. The United Compnay of Philadelphia for promoting American Manufactures was established in 1775 to produce cotton, linen and wool, to compete with England and support the Pennsylvania economy. By 1779 ships left Philadelphia bound for Dublin alone. During that period over 100,000 bushels were exported each year(4).”

“Flax’s Golden Years

By 1818 it could be said that “Pennsylvania probably grows more flax than any state in the Union.” Of 800,000 gallons of linseed oil (a flax byproduct) produced in the country, 500,000 gallons were produced in Pennsylvania.”

“The Rise of Cotton

Markets influenced new trends, and flax-to-linen was trapped between imports and factory-made cotton. By 1808, cotton from Slaters Rhode Island mill was already being sold in Lancaster and other Pennsylvania communities. By 1814 cotton was cheaper per lb. than flax. Between 1815-1830, when the price of Slater Rhode’s ordinary brown shirting was reduced, it out-priced hand-woven cloth like linen.”

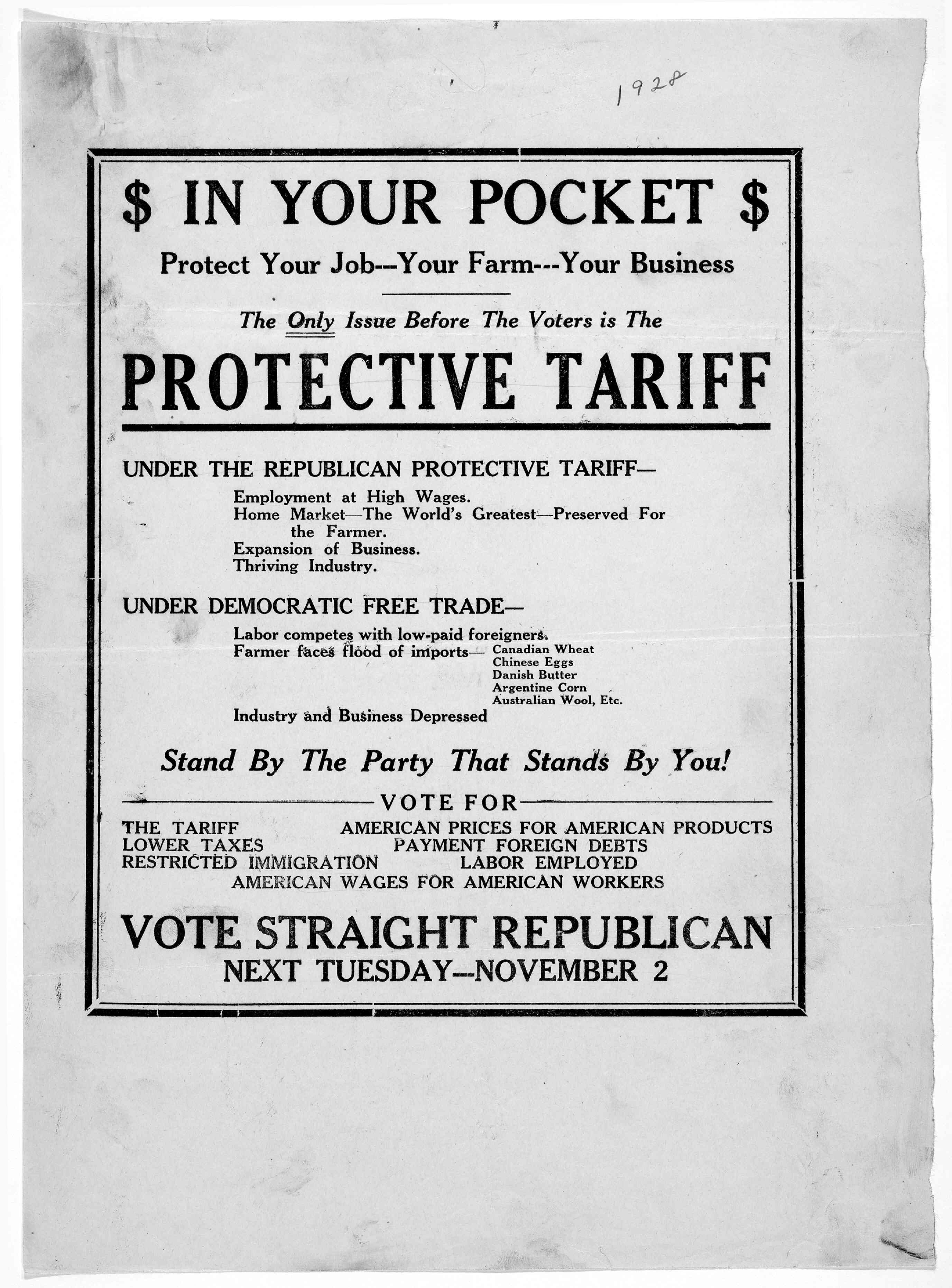

“Flax’s Fall to Cotton

In the 1820s the United Sates was importing more linen than it was making. An article in the Philadelphia Democratic Press urged farmers to grow more flax and hemp saying too much was being imported from Ireland and Russia. The article argued that it was in the best interest of the country to grow more domestic flax and hemp. To counteract such imports, Pennsylvania pro-Jackson legislators helped pass the protective tariff of 1828 specifically covering the states flax and hemp.”

“The Flax War and the End of an Era

As the Civil War began in 1861, it was obvious that the manufacture of linen goods had made little progress in the country. As a household industry, the manufacture of flax is less extensive than formerly, its use having been in great measure superseded by cotton.”

Works Cited: MacMaster, R.K. (2010). Scotch-Irish Merchants in Coloinial America. Ulster Historical Foundation Reid, G.M. (2020). Material Imagination of the Oregon flax Industry. Oregon Dept of Parks and Recreation 2020 Oregon Heritage Fellowship. Arndt, Karl J. R.; Graves, Donald; Colby, Michael; McGill, Paul; Gaugler, Nancy K.; Chrisman, Harry E.; and Parsons, William T., "Pennsylvania Folklife Vol. 35, No. 3" (1986). Pennsylvania Folklife Magazine. 112. digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/paf… Wyatt, S. M. (1994). Flax and Linen: An Uncertain Oregon Industry. Oregon Historical Quarterly, 95(2), 150–175. www.jstor.org/stable/20614577